|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||||||

|

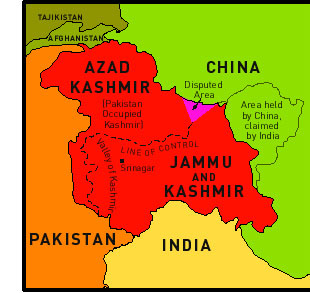

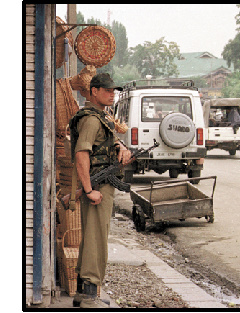

If you ask Alamudin, an octogenarian from Humandar village, what he wants, he responds with a simple one-word answer: "Azadi." After living through 54 years of Indian rule, two wars between India and Pakistan and the past 12 years of terrorism, azadi, or "freedom," is the only thing on his mind. Situated between two giant mountain ranges that make up the Himalayas, the Valley of Kashmir, which is home to about half of the state of Jammu and Kashmir's estimated 9.5 million people, was once known as paradise. Surrounded by arid, high-altitude deserts and huge snow-capped peaks, the valley itself is a wide plain with fertile land and other natural resources. Its green fields, surrounded by the alpine-covered slopes, offer unparalleled scenery. Humandar is one small village out of hundreds in the violence-torn territory, where tens of thousands have been killed since India and Pakistan gained independence in 1947. The village lies along a common route for militants crossing the Line of Control, the

Many in Humandar had pinned their hopes on the Indo-Pak summit held in Agra, India in mid-July. Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee and Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf were meeting to try to iron out their differences on a variety of issues, most importantly the lingering dispute over Kashmir. However, the summit failed even to bring about a joint statement that both sides could agree upon. Since 1947, Kashmir has been not only the subject of a military conflict, but also a political, verbal and psychological one. Kashmir is the feather in India's cap of secularism: the only majority-Muslim state within India's boundaries. At the same time, Kashmir is used to stoke Hindu nationalism by posturing about Pakistani aggression in the state. Before the Indo-Pak summit, Indian politicians, left and right, proclaimed that all of Jammu and Kashmir was an integral part of India. Yet the people of the region have never been allowed the plebiscite required under a 1949 U.N. resolution. On the other side of the border, Pakistani leaders too use Kashmir to fuel hatred and resentment, claiming discriminatory treatment against Muslims by the Indian army. Musharraf, who came to power in an October 1999 coup, became a national hero earlier that year for his role in orchestrating the invasion of Kargil, when militants backed by the Pakistani army and supported with Pakistani artillery crossed the Line of Control to occupy some mountain tops in Indian territory. To the hard-line clerics and military officers who back Musharraf, he is a symbol of pride and strength for a country with a perennial inferiority complex. The military is also no stranger to power in Pakistan, having ruled for more than half of the time since independence. Islamists in Pakistan have declared the fight for Kashmir a jihad, a holy war. When

In the West, people generally view Kashmir as the site of a conflict between Hindus and Muslims. But Balraj Puri, a freedom fighter from independence times and a long-time campaigner for human rights in Jammu and Kashmir, says this analysis is too simplistic. "That is just one aspect of it," he says. "The people of the state are fragmented, confused and disillusioned. All of their leaders have failed them." Since 1989, Indian security forces estimate that 35,000 people have been killed, including soldiers; human rights activists put the number at closer to 70,000 civilian lives lost. In addition, according to Zahir Rudin of the Association of the Parents of Disappeared Persons, more than 4,000 people in Jammu and Kashmir, mostly male youths, have been taken into custody by the security forces and never seen again. In 500 such cases there are specifics on file of who was taken into custody, by whom and when. In some cases, it has been 10 years since the arrest and still there is no word on the whereabouts of the detained. In a startling 50 cases, the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir has actually ordered prosecution of specific officers who have been identified as the culprits, but New Delhi has resolutely refused to grant the required sanction for prosecution. Furthermore, attorney Shahwar Gauhar, of the South Asian Forum for Human Rights (SAFHR), accuses the army of widespread harassment, torture, arson and rape. But the military is not the only culprit in the mayhem that has engulfed this beautiful

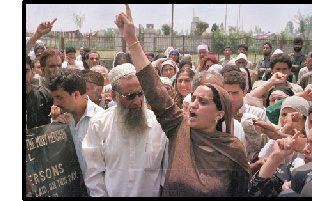

Adding to the mess is the murkiness of who is to blame for recent attacks on civilians. The army blames the militants; human rights activists blame the army. The mujahideen blame the renegades, a group of former militants who have surrendered and now aid the army. Declaration and counter-declaration do little for the Kashmiris. But whom should the Indians and Pakistanis--let alone the United Nations--listen to? With such diversity among its people, who can really claim to represent Kashmir? The most strident claim comes from the All Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC), an agglomeration of political groups in the Kashmir Valley who are mostly pro-Pakistan and all anti-India. The more than 20 parties that make up the APHC vary from stridently pro-independence to absolutely pro-Pakistan. During the Indo-Pak summit the APHC literally created a tempest in a teapot. Musharraf wanted to meet with the APHC leaders, but the Indian government refused. The sides went back and forth over whether there would be a meeting, and the APHC eventually had a 30-minute, one-on-one chat with the general during a tea party at the Pakistani high commissioner's residence, much to the chagrin of the Indian side. At best, the APHC could be said to represent the 37 percent of the population of Jammu and Kashmir who are Kashmiri. What about the remaining 63 percent? The next most vocal group is the elected state government of Indian-held Kashmir, which is ardently pro-India. But most Kashmiris say the elections are rigged, and it's hard to believe otherwise, seeing the overwhelming public sentiment against India. There are a whole slew of other people living in Jammu and Kashmir who have no mechanism for their wishes to be heard. The Ladakhi people, who are mostly Buddhist and have strong links to Tibet, demand territory status within India; the Jammu Dogri, mostly Hindu, want separate statehood; and the Hindu Pandits seek a separate homeland within the Valley. No one heeds their calls. But even the Pandits, 250,000 of whom fled from the Valley of Kashmir in 1990, feel

The other side of the Line of Control is no stranger to this problem. Recent elections for state government in Azad Kashmir (otherwise known as Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, or PoK) were rigged. In this case, the Pakistani administration simply banned parties that did not support the accession of all of Jammu and Kashmir. Demonstrations for independence in the PoK have met with violent repression. So can a representative be found to speak for the people? "The leaders have no right to impose a solution," says N.A. Baba, head of the political science department at the University of Kashmir. "Kashmir is a heterogeneous place. Plurality is important to any solution. Thus, it has to be an imaginative one." Imagination was definitely not in the cards for the Agra summit. But the stalemate was

Vajpayee must keep the Hindu nationalists happy if he wants his coalition government to remain together. He is walking a tightrope, and any movement from the broad consensus will upset the balance of power in a coalition that has already been rocked by scandals. Musharraf also must navigate a web of political intrigue. While he has tried to consolidate power, the militant outfits and religious leaders are still beyond his grasp. And he must please the army brass or risk being toppled by another coup. The Agra summit was the first sign since the Kargil battles of 1999 that Kashmir might see some relief. But since independence, the heads of India and Pakistan have met each other no less that 48 times, with more than 20 summit-level meetings. None of those talks have led to peace, and there was little chance that this one would be any different. Everyone in Kashmir expects things to get worse, not better. Alamudin's dream of azadi again has been deferred. Peter Chowla is a freelance journalist who lives in New Delhi.

|